Waikiki’s Treasured Natatorium

The year was 1921, and the collective American sentiment was one defined by peace and promise for having endured World War I. The new decade brought lushness, richness and a sense of buoyancy that permeated the arts, the sciences and the economy as a whole. Even the world of athletics possessed a particular zeal. Just the year before, the 1920 Summer Olympics were held in Antwerp, Belgium. Given the fact that the 1916 Olympics, scheduled to occur in Berlin, had been cancelled due to the war, athletes and attendees from around the world celebrated in the competition of the 1920 games.

- photos: courtesY hawai‘i state archives

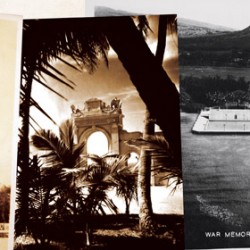

At this same time, Hawai‘i was still an American Territory. But island residents had long been dedicated to the well-being of the United States, especially in this time of war. In 1921, the Territorial Legislature designated funds to create a “living memorial” to honor the thousands of individuals who had fought to defend the country during WWI. The design embraced a dedication to history, a commitment to culture and an allegiance with the nation’s growing athleticism. With funds thus secured, the construction of the Waikiki Natatorium War Memorial began, finding completion in August 1927.

Along the shores of Waikiki, an Olympic-sized, saltwater pool was fashioned. The pool was fronted by an impressive façade, as envisioned by renowned American architect Lewis P. Hobart. The memorial structure features three grand arches, one big and two small. Atop which can be found symmetrically placed eagles and urns, in keeping with the structure’s classical Beaux-Arts architectural design. In the grass in front of the memorial, a large stone can be located with a plaque listing the names of Hawai‘i residents who had served and sacrificed for the sake of humanity in the “war to end all wars.”

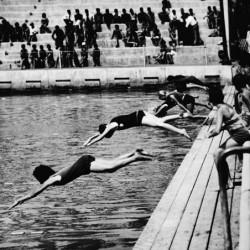

Through the main memorial arch, a walkway leads to the pool. By the late 1920s, the sport of swimming was growing steadily throughout the world for both athletes and spectators. In fact, Hawai‘i son Duke Kahanamoku had already won the 100-meter freestyle in the 1912 Olympics and had returned as an Olympian in 1920 to again take first place in the 100-meter freestyle as both a solo swimmer and as a member of the relay. On August 24, 1927, Kahanamoku, who was an acclaimed surfer and paddler as well, was the Natatorium’s inaugural swimmer. He dove from one of the platforms to the delight of the hundreds of onlookers—some who had traveled just blocks and some who had come from around the world to participate in the opening day festivities.

Throughout the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, Waikiki’s Natatorium would flourish with activity. World-class watermen and women, along with world-famous celebrities, would be drawn to the memorial pool to train, play and pay reverence. In addition to Hawai‘i’s Kahanamoku brothers, Johnny Weissmuller of Olympics and “Tarzan” fame set a world record swimming in the Natatorium. So did Punahou School graduate turned All-American and Olympic swimmer, followed by movie star, Buster Crabbe.

In fact, dozens of noteworthy athletes from around the world would make their way to practice and compete within the Natatorium’s ocean waters. In the 1930s, the decade of both the Great Depression and part of Hawai‘i’s plantation era, an individual named Soichi Sakamoto brought the swimmers he trained on the island of Kaua‘i to compete at the Natatorium. Sakamoto, himself the son of a plantation worker, is famed for taking plantation-raised children and creating Olympic-caliber swimmers. His strategies included training his swimmers in Kaua‘i’s ever-flowing irrigation ditches.

In 1937, with the 1940 Summer Olympics just three years away, Sakamoto used the international event as incentive for his young swimmers to train. Although the 1940 Olympics did not come to fruition, dozens of Sakamoto’s swimmers would not only compete in but also win races worldwide.

President of the Friends of the Natatorium, Mo Radke, details an interesting fact that the water in the Natatorium always seemed faster than that within other pools. He states, “People who swam in the pool would be known to say, ‘That’s the fastest time I’ve ever swum!'” Both Buster Crabbe and Johnny Weissmuller set world records while racing in the Natatorium. In addition to the buoyancy and fluidity within the Natatorium’s watery walls, Radke mentions that, for him, “There is a mana, or spirit, associated with the Natatorium”—one that makes its renovation and restoration imperative for him.

The memorial was built to commemorate the lives of lost loved ones while, at the same time, existing as a place where children and their families could swim and play. But Radke reminds those interested in the Natatorium’s future that it also stands as the birthplace of competitive swimming in the Hawaiian Islands.

Not long after the Natatorium was built, there grew community concern that it was unsafe. Some were concerned that the pool did not have proper filtration. Some were concerned that the nature of the saltwater and coral floor made the pool murky causing a potentially dangerous lack of visibility for swimmers. Unfortunately, the pool suffered years of neglect and was finally closed to the public in 1979.

Since then, however, the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium has become listed on both the National and the State Registers of Historic Places. In 1995, it was named to the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s 11 Most Endangered list.

In addition, just this past May of 2014, the Natatorium was named as the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s newest National Treasure. The organization’s focus is to identify places throughout the country that have especial historic and cultural significance, and it implements plans to save them. The trust explains, “This Treasure designation reflects our commitment to developing a collaborative preservation plan to once again make the Natatorium a vibrant aquatic facility for future generations to enjoy.” After all, for Hawai‘i residents, the Natatorium is remembered as the place where countless children learned to swim and where hundreds of Olympic-caliber swimmers and divers competed to the delight of spectators.

Now, the fates of the front-facing war memorial and the sea-filled Natatorium are actually being considered separately by government officials. One idea on the table is for the pool to be demolished and a manmade beach to be created in its place, with the façade being moved back from the shore. Another idea is for the pool to be completely demolished and replaced by a volleyball venue.

The Friends of the Natatorium, however, feel that equal value lies in all elements of the historic memorial—in the Beaux-Arts arches and the history belonging to those who fought valiantly for peace and freedom and in the Natatorium itself as an unrivaled swimming pool for the Pacific and the world. Thus, they are fighting for the memorial to be restored to all its original glory.

The Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium was created to stand as a symbol of strength and spirit for those who have fallen. However, the memorial itself has fallen into a state of disrepair that simply does not echo of the dignity of those who it was designed to represent.