On Holy Grounds

More than just places of worship, Waikiki’s historic churches have their own stories to tell.

Churches and cathedrals are places of sanctity, worship and faith. Spanning the globe you can find thousands, from Notre Dame de Paris to St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. Besides their spiritual attraction, each in their own way possess an architectural splendor, a castle-like enchantment inviting dedicated faithful along with the just plain curious through their entryways.

Churches also possess a historic element, heightening a church-goer’s experience through stories and vintage images of time and place.

Christianity and Catholicism are very much a part of the societal developments of Hawai‘i over the past 200 years. For a view of old Hawai‘i, Waikiki’s St. Augustine bythe-Sea and St. Mark’s Episcopal churches are landmarks of nostalgia and significance.

The first arrival of Christianity came from Protestants, who in 1820, traveling from New England, anchored off the shores of Kohala and Kailua on the island of Hawai‘i.

While en route to the islands, the Hawaiian religious or kapu system had been abolished and practiced faith was in certain disorder.

Within just a few years, thousands of native Hawaiians were enrolled in Christian education and faith-based systems island-wide.

In 1827, the first Catholics landed on Hawaiian soil and almost instantly were subjected to persecution from Protestant Congregationalists and converted Hawaiian royalty, including Queen Ka‘ahumanu. Despite this, Native Hawaiians grew intrigued by Catholicism.

“Hawaiian people were very curious because they [Catholic missionaries] had on their long black cassocks which drew in heat. They were very patient. Hawaiians enjoyed listening to them singing Gregorian chant and the cymbals of that time,” says Father Lane Akiona of St. Augustine’s by-the-Sea.

“When Catholicism came, many Hawaiians were attracted because we have lots of statues, rituals and symbols. It was like supplementing the old abolished traditions for some.”

As Ka‘ahumanu noticed a decrease in Protestant attendance, she condemned all Catholic converts to hard labor and imprisonment. A prison was located just blocks from where St. Augustine now stands on Kalakaua Avenue, but has since been torn down. It was this treatment, which led to many Catholic converts fleeing to outskirt areas of O‘ahu.

In 1839—upon French military threats towards King Kamehameha III—a proclamation was rendered by the government, ensuring the freedom of Catholic worship.

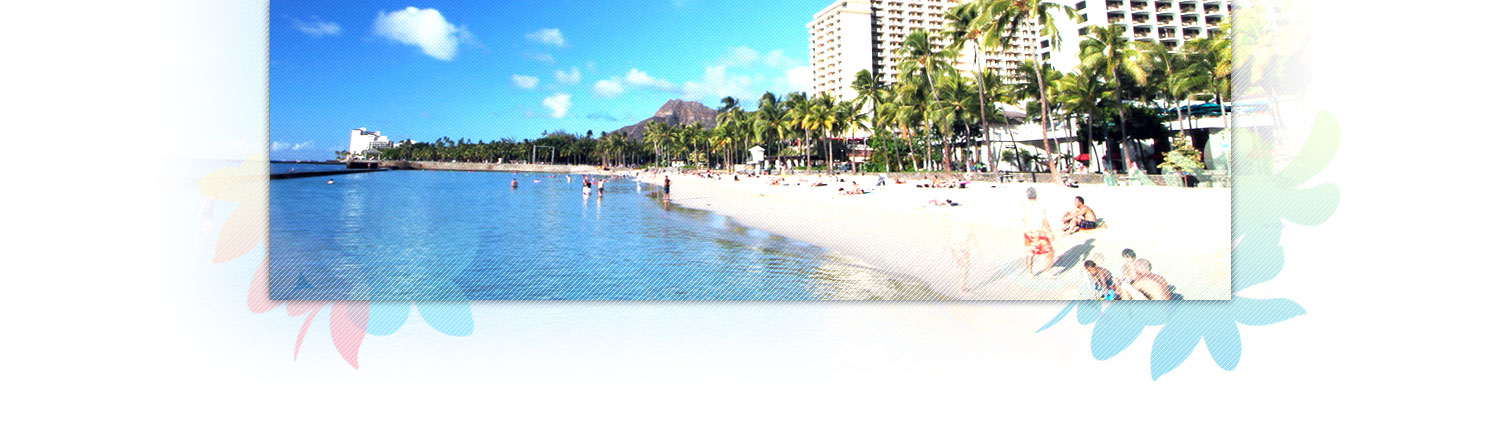

The original St. Augustine church was established on the quiet sand of Waikiki beach.

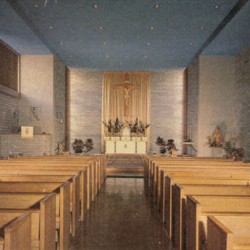

Photos courtesy of St. Augustine’s By-The-Sea and St. Mark’s Episcopal Church

- St. Augustine’s By-The-Sea is located on Kalakaua Ave.

- St. Mark’s Episcopal Church

- St. Mark’s Episcopal Church

- St. Mark’s was established in the early 20th century as an outreach parish of the St. Andrew’s Cathedral.

- Ground-breaking of the existing St. Mark’s building took place in 1951.

- Celebrating a milestone at St. Mark’s.

- The day school at St. Mark’s provided a quality education for its students.

- At the end of World War II, St. Mark’s congregation outgrew its original buildings.

- St. Augustine’s has gone through many renovations over the past century.

“The original was right on the beach before all the developments took place. It had just a coconut-frond thatched roof and basically served Hawaiians,” adds Akiona.

As the Spanish-American War boiled, a large military presence grew in Hawai‘i and a demand for a larger church was called for.

In the late 1800s, across the beach on what was tiny Ohua Lane, a more permanent home for St. Augustine’s was erected.

“The original lattice church was built without windows. The thing that people loved about it [was] the birds would come rest on it. It was very natural, very Polynesian,” adds Akiona.

The church has undergone many renovations and expansions over the past 100 years. In the 1960s the most current church was erected to accommodate the increasing tourist assembly. Its blessing was held in August, 1962. Earlier this century, the church underwent major renovations in preparation for the 150th anniversary.

“We take into account our cultural elements of Hawai‘i, from the music we use and our hospitality. We always try to incorporate the Hawaiian concept ho‘oponopono which is forgiveness and compassion,” Akiona says.

A few miles from St. Augustine and Waikiki beach on Kapahulu Avenue, St. Mark’s Episcopal Church—an outreach of St. Andrew’s Cathedral located in downtown Honolulu—was established in what used to be a large agricultural area with small farms, chicken coops and duck ponds.

Early 20th-century neighbors of the area, mostly of Hawaiian and Chinese descent had no place of religious worship at that time. As many relatives congregated at St. Andrew’s, the idea to start an outreach parish was sprung by the ‘Iolani Guild of Hawaiian Congregation.

After the initial Sunday school grew in popularity, a small wooden chapel was constructed in a cozy grove, with native kiawe trees surrounding.

Queen Emma, wife of King Kamehameha IV—who had invited England representatives to establish Anglican Church in Hawai‘i—was honored in the naming of the chapel as she died on St. Mark’s Day, April 25, 1885. Chosen as the parish’s minor patron, it is noted that Queen Emma preferred the Hawaiian island chain to have gone to the British rather than America.

A day school was established near the grounds of the parish hall, and St. Mark’s was determined to hold a high quality of education as a top priority for those who attended.

As World War II concluded, the congregation was outgrowing its quaint quarters and a replacement church was in order. In 1951, the groundbreaking was held for what now stands as St.

Mark’s Episcopal Church. Many artifacts within combine English sentiment with Hawaiian lore, including a koa wood altar. Queen Emma is also depicted in a stained-glass panel wearing a traditional Hawaiian maile lei draped over her shoulder representing a deacon’s prayer shawl.

Throughout its history, St. Mark’s has always been an invited and accepted parish. It is known to be welcoming of the gay, lesbian, bi-sexual and transgender community, particularly in the 1980s when other congregations were not.