Remembering World War II

How the Day of Infamy Affected Our Beloved Waikiki

For residents and guests either vacationing or going about business in Waikiki on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, the initial reaction to the Pearl Harbor bombings, surprisingly enough, was not panic.

For the previous two years before the bombings, tensions had risen between the United States and Japan. As the Japanese military began to creep closer to American communications, fortifying the Marshall Islands, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt saw it imperative to establish a strong naval presence in the Pacific. In 1940, Roosevelt moved the main United States Pacific Fleet from California to Pearl Harbor naval base on O‘ahu. For the nearly 18 months prior to the bombings, the United States Navy conducted mock battles and air maneuvers. These routine practices were as common as hearing fire or police department alerting horns.

“The attack on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941 initially confused many on the island of O‘ahu, although some wondered why such a thing was happening on a Sunday morning,” says Desoto Brown, Hawaiian historian and Bishop Museum archivist.

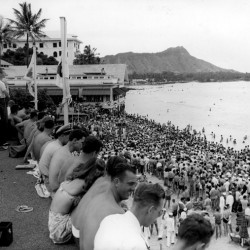

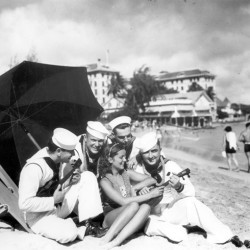

- Servicemen crowd Waikiki Beach during what appears to be a beauty contest that was part of a Kamehameha Day celebration. Photo courtesy of Ian Lind Collection (www.ilind.net)

- Duke Kahanamoku (far left) on Waikiki Beach during WWII. Photo courtesy of Ian Lind (www.ilind.net)

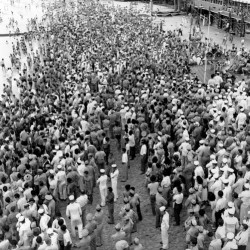

- Thousands of servicemen flock to a Kamehameha Day celebration staged by the Junior Chamber of Commerce in 1944.

- Barbed wire lined the beaches of Waikiki to protect against seaborne invasions. Photo courtesy of NPS Photo Archives at Valor

- The popular Kamehameha Day celebration was undoubtedly a welcome respite for the servicemen who gathered for the standing-room only festivities.

- Martial law in Hawai`i was in force from Dec. 7, 1941 through late 1944. Here, sailors pose on the beach. The Moana is visible in the background. Photo courtesy of NPS Photo Archives at Valor

- WWII servicemen gather in the courtyard below the iconic banyan tree at the Moana. Photo courtesy of Starwood Waikiki

“Gradually, the word got out that this was no practice, but ‘the Real Mc-Coy!’ as announcer Webley Edwards forcefully said on radio station KGMB.”

At five minutes to 8 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941 a Japanese dive-bomber appeared through a sheet of clouds hanging over O‘ahu. The dive-bomber, marked with the Rising Sun symbol of Japan was followed by 300-plus warplanes, armed with bombs and ammunition intended for naval destruction.

“The surprise attack had to be so quickly executed that the Japanese could not waste any ammunition on sideline, civilian areas. It was possible for people to stand in the street or on the beach and watch the planes and smoke in the distance,” says Brown— who notes some U.S. anti-aircraft shells which did not explode in the air, landed in the waters off Waikiki, one even striking Lewers Street in Waikiki, creating a small crater and breaking windows of a new, yet unoccupied apartment building.

“Friendly-fire was raining down from every angle,” says National Park Service chief historian, Daniel Martinez.

Immediately following the bombings at Pearl Harbor, martial law was declared for the entire territory of Hawai‘i and the initial early morning curiosity quickly shifted to urgency and uncertainty on the part of the military and civilians.

“By mid-afternoon the Army had taken charge,” adds Martinez. “It was absolute chaos how the island was reacting. You had a city in a lot of fear. This was a take on the entire island of O‘ahu, not just Pearl Harbor.”

For the days and weeks following the bombings the usual calm, tranquil atmosphere of Waikiki was replaced by attitudes of turmoil and defense.

Waikiki’s beaches were quickly lined with barbed wire to protect against Japanese seaborne invasions. Strict blackout and curfew orders were enforced island-wide. Tourists and residents alike were to be in their homes or hotel rooms with lights out by sunset each day.

1941 Waikki is a fraction of what stands before you today. There were only two main hotels lining, what wasn’t even famous Waikiki Beach yet. The Moana, or as her title has been tailored, “The First Lady of Waikiki” and The Royal Hawaiian were the two mainstay hotels. Other establishments of Waikiki at the time would have been the Halekulani hotel and Willard Inn on Kalia Road. Small businesses such as an upscale clothing store, Kodak Hawaii and Waikiki Pharmacy sprinkled themselves in the Waikiki Theater Block at this time.

There were also a few bars and restaurants, including Tropics and Waikiki Tavern, located very near to where the current Duke Kahanamoku statue stands today.

Those two prominent hotels, The Moana and The Royal Hawaiian, remained open throughout the duration of martial law, which was not lifted until Oct. 24, 1944.

Although Hawai‘i was not yet an American state, support came from every corner, even from visiting athletes.

The Willamette Bearcat football team was in Hawai‘i participating in the Shrine Bowl football series on Dec. 6, 1942. Their intentions to tour the island on Dec. 7, 1942 were cancelled due to the bombings.

“Many of Willamette’s coaches were ex-officers from World War I. Immediately they stepped in with their team. Weapons were issued to the players and the coaches took charge, drilling the team and setting up positions on Waikiki Beach,” says Martinez.

At the same time, University of Hawai‘i ROTC members banded together, scouring more internal areas of O‘ahu in defense of Japanese soldiers who may have snuck onto the island through more remote locations.

In the months following the bombings, the Navy Recreation and Morale Office leased The Royal Hawaiian Hotel. Within weeks, the tourist palace was transitioned into a rest-and-relaxation headquarters for Navy personnel, mostly for those returning from duty in the Pacific.

The Moana remained open as a guest hotel, and not a room went vacant throughout the entirety of World War II.

For economic security, the U.S. government withdrew all regular American currency, replacing them with specially printed Hawai‘i notes. With the possibility of Japanese invasion looming and in the event of an invasion, the new ‘Hawai‘i’ notes would have become invalid if Hawai‘i had been taken.

Although a cloud of anxiety overhung O‘ahu for years following the Pearl Harbor bombings, those in Waikiki made the best of it as they could, trying to restore a sense of normalcy in a time of doubt and unrest.

Christmas and New Year’s Eve dinners and concerts scheduled before the bombings, took place as usual in the winter of 1941. Dancing, sports activities and social gatherings at both the Moana and Royal Hawaiian gave servicemen glimpses of much-needed relief in between tour duties.

Being in a small, isolated island community during such an unnerving time was not paradise, but kama‘aina and servicemen did an extraordinary job, preparing for more unexpected attacks.

Development was at a standstill in Waikiki during WWII, as all building materials were set aside for the war efforts. It wasn’t until a few years after the Allies had overcome the Axis countries during WWII that Hawai‘i and Waikiki began to flourish once again. The war years were a trying time for Waikiki, but it paved the way for the rise of its popularity for decades to come.