Picture Perfect

A fabled hula show in Waikiki had its beginnings at the same time as the introduction of color film—the idea for travelers to take amateur color photos of a vibrant, authentic Hawaiian experience was born.

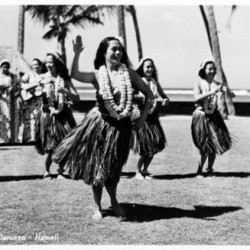

The vibrant and bountiful colors, along with the archetypal sights and sounds of the Hawaiian Islands, have rarely been celebrated as thoroughly as during the six-decade-long run of Waikiki’s Kodak Hula Show. An elaborate production featuring both the traditional and modernized song and dance of Hawai‘i, the Kodak Hula Show existed as a free, outdoor musical production for visitors and residents.

The show found its genesis in 1937 as the brainchild of Fritz Herman, then vice president and manager of the Kodak company’s Hawai‘i branch. Only two years previously, in 1935, Kodachrome film had been introduced to the world, inviting amateur photographers to explore on their own the glories of color. Herman’s vision for the daytime hula show was for spectators to have the opportunity to take photographs of island performers, thus promoting color picture taking alongside a taste of the Hawaiian Islands.

Many people would save for years to travel to Hawai‘i just to experience the warmth and magnificence promised by a trip to a small chain of islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Being gifted with this extension of this spirit through the Kodak Show, in a way that provided an introduction to “real” Hawaiian performance and celebration, brought decades of smiles to the faces of tourists. And it was through these smiles that the Kodak company found its commitment to the show for so many years. During the primary years of the Kodak Hula Show, photographs within the pages of Time and Life magazines were the only places people could catch glimpses of the many cultures around the world. Once Kodak created film for the average traveler, similar images could be captured by almost anyone.

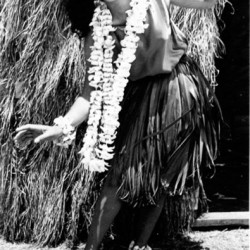

- Clara Inter, “Hilo Hattie” dancing to “The Cock-eyed Mayor of Kaunakakai” at Kodak Hula Show circa 1937

The 1930s and ‘40s would mark the beginning of a staunch focus on tourism in Waikiki. Commercial air travel would be a few decades away. However, in what was still the Territory of Hawai‘i, trans-Pacific luxury ocean liners would bring thousands of visitors to Hawai‘i each year. Those who attended the Kodak Hula Show could partake in a compelling cultural experience very unlike that from where they came, even if just for an hour or two.

The Kodak Hula Show provided attendees with a gleeful and jovial celebration of all the melody, movement and magic associated with the Hawaiian Islands while finding a dedication to Hawai‘i’s rich and intricate culture and traditions. Performers throughout the years have recounted the joy they themselves experienced sharing memories from the shows with an awareness that their production helped nurture a unique island awareness for many tourists over the years.

Rapid and lively ‘ukulele would accompany the dancers. Some fast-moving and some lilting and all adorned with flowers, dancers invited viewers to join in with their own toe tapping as they wove about one another like the lei around their shoulders. Other dancers, more methodical, would enter the performance area in sleek lines and sedulously exercise precise movements. Led by the rhythmic beating of the ipu, the gourd drum, their performance provided a collective remembrance of the past.

The original venue for the Kodak Hula Show was Sans Souci Beach, oceanside of Kapi‘olani Park. Within the land division traditionally known as Kapua, this beachside area of Waikiki was called by the French name “Sans Souci” for a time, congenially translated in English as “carefree” or “without worry.”

In 1952, the pristine outdoor amphitheater the Waikiki Shell was crafted to resemble a giant white seashell on the north end of Kapi‘olani Park, about a half a mile from the beach. The Kodak Hula Show was moved to the Shell in the 1970s and, upon the grounds, would continue to welcome audience members to share in the general culture of the Hawaiian Islands. With eventually up to approximately 40 dancers, many of whom were members of the Royal Hawaiian Girls Glee Club, performers and visitors alike could revel in melodies and traditions unlike any other.

Today, many of the islands’ residents comment with regret about how, for one reason or another, they never made it to see the Kodak Hula Show. As the daily celebration of the song and dance of the Hawaiian Islands had, for decades, been a defining element of the Waikiki scene, many assumed that the production would go on forever.

However, such would prove not to be the case. Kodak withdrew its sponsorship of the show in 1999, after more than sixty years. Approximately two years later, the production would be reawakened by the Hogan Family Foundation. Renaming the show after their own travel company, the family would sponsor the Pleasant Hawaiian Hula Show to the tune of approximately $500,000 annually for another two years. However, in September of 2002, the days of Waikiki’s famous Hula Show were over.

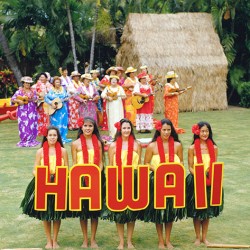

The blueness of Waikiki’s sea and sky along with the greenness of the picturesque Diamond Head for years provided the backdrop for the famed Kodak Hula Show. The colors that most clearly identified the show itself could be found in the iconic, oversized letters brought out by dancers at the show’s beginning and end—in red and yellow and spelling out the words “HAWAII” and “ALOHA.” Significant is the fact that these very same two colors are not only the ones chosen by the Kodak company in the 1930s for their own logo but that, for centuries within the Hawaiian Islands, red and yellow had also been the distinguished colors designating royalty, or the ali‘i status, of many of the islands’ people. As such, even in a commercial sense, times of the past once again became linked to the present.

During its run, the Kodak Hula Show invited thousands each week to experience “The Aloha Spirit” that had come to be synonymous with Hawai‘i. This spirit, as displayed through the show and, as such, was coupled with an echoing sense of the islands’ allure, continued to draw visitors from around the world for decades. The last series of letters carried proudly by the show’s performers spelled the word “PAU,” or “all done,” thus bringing a final show— and an era—to a close.

Photos: Courtesy Hawai‘i State Archives