Waikiki’s Waterway: Ala Wai Canal

From taro fields and fish ponds to present-day landmark, the history of Ala Wai Canal goes hand-in-hand with the history of Waikiki.

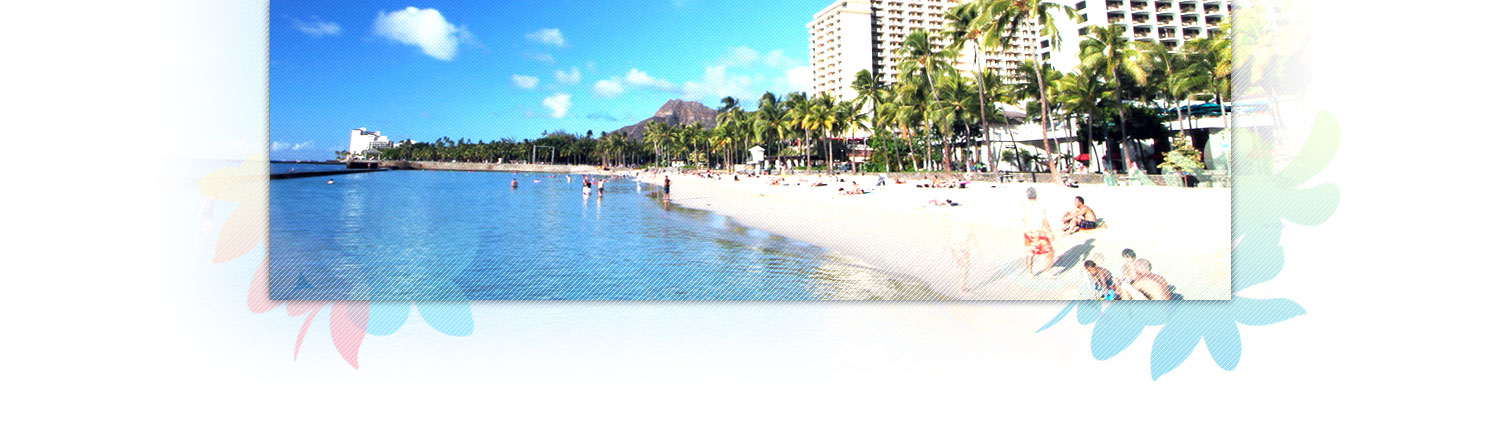

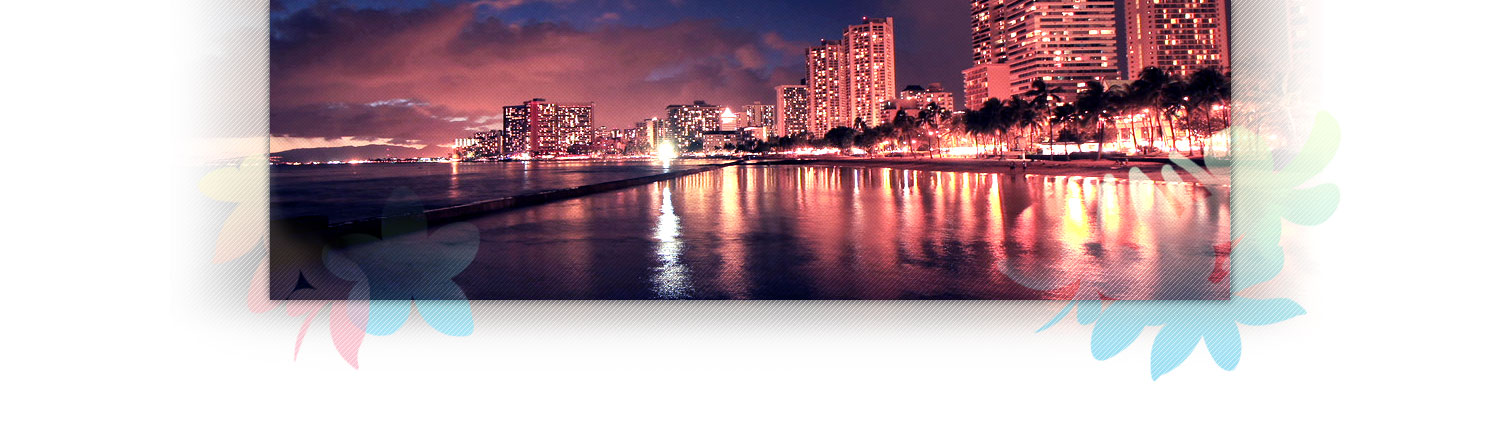

Not far from and running parallel to Waikiki Beach lies the “quite marvelously beautiful” artificial waterway called the Ala Wai Canal. One end of the canal opens to the sea, while the other end comes right up to the Waikiki-Kapahulu Public Library. Lining the canal’s mauka shores are colorful outrigger canoes, a lush golf course, and even a community garden. But, originally envisioned as “a Venice in the midst of the Pacific,” the Ala Wai Canal exists as feature of Waikiki that has a complicated history.

This waterway is said to have been the brainchild of Lucius E. Pinkham, president of the Territorial Board of Health from 1904 to 1906 and governor of the Territory of Hawai’i from 1913 to 1918. Pinkham set out to change Waikiki’s primary landscape from that of wetlands to solid land, citing that the swampy area presented a threat to public health. Honolulu development mogul Walter Dillingham was hired to dredge enough fill to rid Waikiki of her wetlands, with the intent of establishing the area as a rural haven for the wealthy and the socially elite and as an ideal destination for visitors to the islands. As part of the early 1920’s Waikiki Reclamation Project, material excavated by Dillingham’s Hawaiian Dredging Company was distributed throughout acres of Waikiki’s marshes, ponds, and springs. The area from which the material was dredged, would become the Ala Wai Canal, measuring almost two miles in length.

Centuries before the dredging, Native Hawaiians had crafted lo’i (taro terraces) and loko (fishponds) throughout the Waikiki area, thus establishing a remarkable, self-sufficient agricultural and aquacultural community. Naturalist Archibald Menzies, who travelled to O’ahu in 1792 with Captain George Vancouver, commented specifically on the elaborate irrigation system that had been created by pre-contact Native Hawaiians.

- Waikiki – Ala Wai Canal

- Moena Park & Ala Wai

- Ala Wai Boat-house

- Waikiki – Ala Wai Canal fishing 1931

- 1972 Ala Wai Canal

We pursued a pleasant path back [from the shores of Waikiki] into the plantation, which was nearly leveled and very extensive and laid out with great neatness into little fields plated with taro, yams, sweet potatoes and the cloth plant. And the whole was watered in a most ingenious manner by dividing the general stream into little aquaducts leading in various directions so as to be able to supply the most distant field…

It was rainwater from the Ko’olau mountain range that travelled to the Makiki, Palolo and Manoa valleys feeding underground springs that provided fresh water for these pristine wetlands.

However, from 1778 to 1890, hundreds of thousands of Native Hawaiians would perish, largely due to diseases introduced by early European explorers. The decrease in population left many of the lo’i and loko unattended and no longer nurtured in the traditional manner. In the early 1900s, Waikiki’s wetland terraces and ponds would see a renaissance of sorts. The booming sugar industry brought migrant workers from China and Japan, among other countries, and with them came the need for rice. Asian residents restored many of the water-based agricultural lands as rice fields. But shortly they would lose their farms and their livelihood, and remaining Native Hawaiians settlements would be overtaken, with the movement to recreate Waikiki as a place for tourists and for merchants to establish their businesses and take up residence.

The Waikiki dredge and fill project would begin in 1921 and find completion in 1928. The idea behind the Ala Wai Canal was that it would flow through Waikiki as a “water sports park” inviting boaters and swimmers to enjoy an alternative to the nearby beach. With the classification of the Ala Wai as “one of the best courses for crew races in the U.S.,” the Yale rowing team trained on the canal on their way to Melbourne, Australia, for the 1956 Olympics. Drawing on the romance associated with Venice, Italy, it was even imagined that gondolas would be added to the Ala Wai experience. For decades, residents and visitors alike would line the shores of the waterway. Fishermen, set out on small platformed piers, would catch fish for their families, and others would use the canal for clamming and crabbing.

Unfortunately, over the years, the Ala Wai’s design proved to be the cause of a true public health risk. There exists an entrance to the canal, toward Ala Moana Beach Park, but there is not a corresponding exit. The waterway’s planned circuit was never completed. Even before the canal was finished, engineers determined that, if the canal had followed the original design, opening up toward Kaimana Beach, currents would take any unwanted refuse through the Ala Wai Canal and directly to the most ideal section of Waikiki Beach. Without an outlet, the canal’s water became stagnant and polluted. Adding to that, in times of emergency, the Ala Wai was used as a sewer system outflow.

Thus, today, there are warnings to neither swim in the canal nor eat anything caught within it. Because of the pollution, additional concerns exist regarding what would happen if rainstorms caused the canal to overflow, essentially flooding Waikiki.

On any given day, the Ala Wai Canal still bustles with activity and glistens with grandeur. In spite of the concerns associated with the waterway and its history, the Ala Wai remains a tranquil and attractive addition to the Waikiki landscape. Bordered by a sidewalk that is frequented by walkers and runners, the canal is seen by many as a significant feature within what Walter Dillingham predicted would be “one of the most attractive sections of the city.” People can be seen throughout the year photographing the rising sun as it literally lights up the entire Ala Wai Canal with the day’s first brilliance.

PHOTOS: COURTESY HAWAI’I STATE ARCHIVES